There is much to discuss about this clock purchased on ebay recently from a seller in the UK. Certain features of the clock discussed in more detail below (age, previously unreported label, movement closely associated with Sperry & Shaw, a label printer local to Sperry & Shaw) lead me to believe that this clock is a counterfeit Jerome that was sold overseas. While the clock itself is just an ogee, it was a witness to theft and exploitation of Jerome’s name by unscrupulous New York makers. That fact lends the clock a significance that far outweighs its objective value as an ogee in rough condition.

A little history first, before looking at the clock. As told by Chauncey Jerome in his autobiography, History of the American Clock Business…”:

“Merchants from the country…had heard about Jerome’s clocks which had been retailed about the country, and that they were good time-keepers, and would enquire for my clocks. These New York men would say that they were agents for Jerome and that they would have a plenty in a few days, and make a sale to these merchants of Jerome clocks. They would then go to the Printers and have a lot of labels struck off and put into their cheap clocks, and palm them off as mine. This fraud carried on for several years. I finally sued some of these blackleg parties, Samuels & Dunn and Sperry & Shaw, and found out to my satisfaction that they had used more than two hundred thousand of my labels. They had probably sent about one hundred thousand to Europe.” (emphasis added)

As reported in Chris Bailey’s From Rags to Riches to Rags:

“In the latter 1840’s Jerome began to have keen competition and many ogee clocks were being produced, often with inferior movements, in an attempt to undersell him. Several firms located in New York City were involved in this and some of them claimed to be his agents to secure clock orders. Jerome claimed that two firms, Samuels & Dunn and Sperry & Shaw, had been putting labels printed with Jerome’s name in these clocks. He sued these two firms…” (emphasis added)

It is not known whether Jerome recovered any money from Sperry & Shaw for fraudulent use of his name, but he did win his suit against Samuels & Dunn and received $2,300. His suit actually requested $20,000 in compensation, but Jerome states in his autobiography that the foreman of the jury later told him that one of the jurors was bought, presumably by someone representing Samuels & Dunn.

According to the label, it was made by Chauncey Jerome of New Haven, CT. The label was printed by Wells, Brownson & Co. of 56 Gold St., New York. Based on information from New York city directories, Wells, Brownson & Co. were in business around 1846. Brownson & Co. (without Wells) are found in the 1845 directory, and Wells (estate of Chas.) & Brownson are listed in the 1847 directory. The label is not one ever reported (to the best of my knowledge) for a Chauncey Jerome clock.

Close-up showing the remnants of the printer’s line. Enough is preserved to identify the printer as Wells, Brownson & Co. According to Google, the printer’s office was a 7 minute walk from Sperry & Shaw’s location at 10 Cortlandt Street.

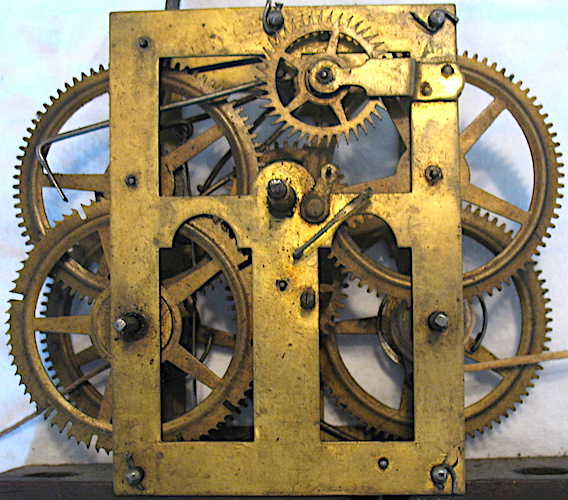

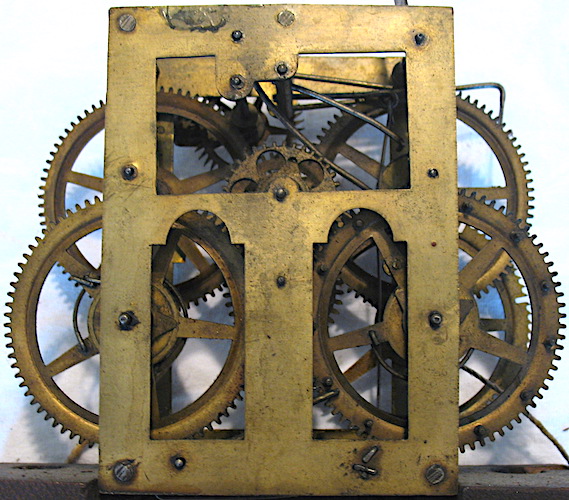

Based on Snowden Taylor’s classification scheme, the movement is a type 2.(10)22, maker unknown. In his more recent working files, he renumbered this a 2.(10)24. His files show that the movement was used by many “makers”, but Jerome was not among them. What’s particularly interesting is that, of the 28 reported examples of this movement, 12 are associated with Sperry & Shaw clocks. The next closest in reported users of this movement is F.C. Andrews, with four examples.

Rear view of the type 2.(10)22 (renumbered 2.(10)24) movement.

Dial, movement, and clock case all appear to be original. The holes in the seatboard for the retention pins line up with corresponding holes in the vertical rails. The seatboard could not have once held a Jerome movement, because the plate posts that are fastened to the seaboard by J-hooks are further apart on a Jerome movement. Similarly for the dial: Jerome winding arbors are 81mm apart, whereas the Sperry & Shaw’s are 75mm apart. The facts support this clock being one of the counterfeit Jeromes marketed overseas by Sperry & Shaw, using Jerome’s name to take advantage of his hard-fought reputation. Adding insult to injury, an article was published in a New York paper after Henry Sperry’s death stating that “he was the first man who went to England with Yankee clocks.” Further, as Jerome writes,

“After I had sent over my two men and had got my clocks well introduced, and had them there more than a year, Sperry & Shaw, hearing that we were doing well and selling a good many, thought they would take a trip to Europe, and took along perhaps fifty boxes of clocks.”

Jerome’s claim that he was the first to introduce American clocks in 1842 is supported by researchers and available documentation. According to Chris Bailey (NAWCC Bull. No. 256, Oct 1988), Sperry & Shaw are first listed in New York 1843-1844 directories (published mid-year in 1843) as clock dealers; they show up the following year as clock manufacturers. Jerome’s timeline is supported by the fact that Sperry & Shaw formed their partnership a year or more after Jerome first exported clocks to the UK. So, although history might rightfully credit Jerome for opening up the overseas market, a New York paper gave that credit to Sperry, who, in fact, used Jerome’s name to sell clocks overseas.