A reeded pilaster & scroll top clock has been on my wish list for quite a few years, but circumstances have never been quite right until earlier this summer. On a beautiful day in early August, my wife and I drove to the coast of Maine to pick up the clock.

The clock was made by Jerome, Thompson & Co. around 1826-1827. The company was a partnership between Chauncey & Noble Jerome and Asa Thompson. The company filled the time between Jerome, Darrow & Co. (1824-1826) and Jeromes & Darrow (1828-1834). These clocks get their name for obvious reasons: the door frame has reeded pilasters (“flat” columns, if that isn’t an oxymoron) and a scroll top that follows the style used in pillar & scroll clocks. The pilasters on this clock have exquisitely carved capitals, which are typical of these clocks. Jerome’s first use of the reeded pilaster & scroll top case was with Jerome, Darrow & Co., and he continued using the case through the early years of Jeromes & Darrow. It probably went out of style with the introduction of the bronzed looking glass clock around 1835 or so. To the best of my knowledge, Jerome, Thompson & Co. only used reeded pilaster & scroll top cases.

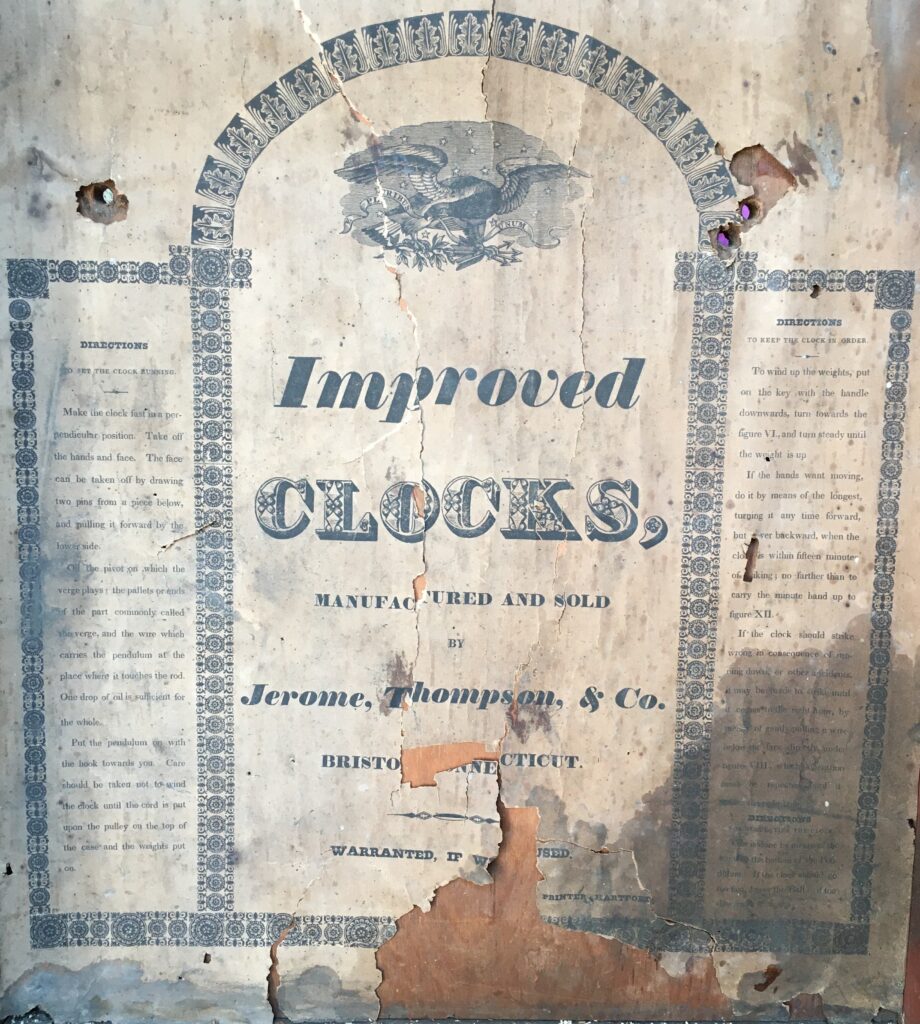

Although the printer’s line (aside from “PRINTER, HARTFORD”) is lost, these labels were printed by Philemon Canfield. Jerome used Canfield labels (exclusively?) almost until the end of the C. & N. Jerome period (1834-1838).

Clocks by Jerome, Thompson & Co. used groaner movements made by Chauncey Boardman. Jerome’s use of Boardman movements extended from the dwarf tall case clocks assembled by Jerome in 1824 in East Randolph, MA into the Jeromes & Darrow period and probably ended around 1828 when Noble Jerome developed a 30-hr wood movement referred to as the “thin” movement. The earliest groaners were mounted on seatboards; later ones (like this one) were attached to the backboard using wooden cleats at top and bottom.

The selling point that hooked me was the wonderfully executed, splayed French feet. Every Jerome reeded pilaster & scroll top clock I have ever seen (regardless of which of Jerome’s firms made it) has been without feet. Whether original or not, the feet seem to fit the case perfectly. French feet were a feature of Federal furniture and, by 1826, were on their way out of style. The fact that fashion preferences were turning away from French feet by the mid-1820s may support the feet being original on this clock, because it seems less likely (though certainly not impossible) that someone would have added a feature that was out-of-style after the clock was made. I’ve included several views of the bottom of the case, and I’ll let you be the judge whether there’s anything that permits establishing the originality of the feet.

In the three photos above, along the back edge of the bottom of the case, remnants of paper glued to the base are present, extending under the structural element that provides strength to the right rear foot. I have no idea what to make of this. The feet show considerable age.

Aside from some obvious repairs to veneer, most of the mahogany veneer on the skirt is similar (in grain and coloration) to the rest of the case.

Elements of the skirt and feet (for example, see the middle humps between the feet on each side) aren’t perfectly symmetrical. Is this evidence of restoration or just typical of period handmade construction?

This last photo shows construction details of the scroll top.

From a purely academic standpoint, establishing whether the feet are original or not would be great. Ultimately, though, I don’t think that would affect my feeling that, aesthetically, they’re a wonderful complement to the case.