On first glance, I thought this clock was a smaller version of S.B. Jerome’s design patent (959, 20 Oct 1857) for a clock case that I have seen referred to as the “Square Rose”. [Incidentally, if anyone knows the origin of the name “Square Rose” I would love to hear it.] Comparison to the patent drawing quickly eliminates that assumption. Nonetheless, there are similarities between the clock and the patent case that lead me to believe that it was inspired by the patent. The clearest similarities can be found in the cornice. To the best of my knowledge, S.B. Jerome never manufactured a clock following the 1857 patent specifications, which is the reason I was so interested in this clock. The only examples I have seen (in 30-hr and 8-day weight-driven versions) were made by the Waterbury Clock Co. at around the time Chauncey Jerome worked for Waterbury (fall of 1856 to spring of 1857), prior to the issuance of the patent.

S.B. Jerome’s clock-making activities aren’t clear in the years immediately following the 1856 bankruptcy of the Jerome Manufacturing Co., of which he was the Secretary. Most clocks having features patented by S.B. Jerome appear to be from around 1863 and extending into the 1870s. Jerome was issued five design patents during this period (1763, 16 Jun 1863; 2057, 9 May 1865; 4278, 9 Aug 1870; and 4338, 6 Sep 1870). The New Haven City Directory lists him as a clock maker from 1863 to 1878, after which (1879-1882) he is associated with “Jerome & Co.”. From relatively scarce labels on detached lever marine timepieces, S.B. Jerome was operating a business for a period under the name “S.B. Jerome & Co.”. All other clocks bearing his patent features appear with labels for either Jerome & Co. (note the absence of “S.B.”) or S. Peck & Co (a daguerreotype manufacturer). In the 1869, 1870, and 1871 New Haven Directories Jerome’s business address, 81 Day St., is the same as Peck’s.

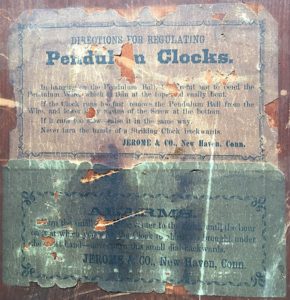

The label, indicating the clock is the product of Jerome & Co., is glued to the back of the case. Labels on clocks having S.B. Jerome patent features are usually of three varieties: wood panels on the inside of the door (serving to retain and protect a decorative glass or composite panel), cardboard labels also on the inside of the door; or paper labels (either attached to the back of the case or glued to a wood panel mounted on the inside of the door). Most shelf clocks tend to have labels on the inside of the door. Others, like octagon timepieces and small shelf timepieces with lever escapement movements, have paper labels glued to the back of the case.

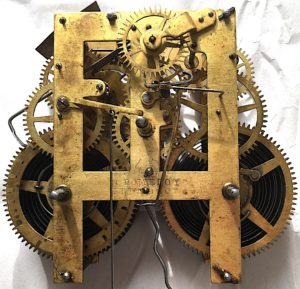

As is typical of shelf clocks having elements based on S.B. Jerome’s patents, the movement was made by Noah Pomeroy. In this case, the movement is an 8-day version with external alarm and is stamped “N. POMEROY/BRISTOL CT”. Pomeroy’s movements had either pinned plates (believed to be earlier) or plates held together with screws. Although my memory may be faulty, I believe only the pinned plate movements had a Pomeroy maker’s stamp (and not all of those had a stamp). Based on the association of screwed plate movements with labels listing Jerome’s October 1870 patent, I suspect this clock dates to the mid- to late-1860s.

Another feature common to clocks attributed to S.B. Jerome is the use of decorative paper glued to the backboard inside the clock, or, in the case of marine timepieces, glued to the back of the case. Multiple patterns (at least five) have been observed on these paper backings.

An unusual and unexplained feature of this clock is the presence of two pieces of wood attached to the backboard on which the movement and gong base are mounted. The wood pieces are attached with the same style of wire nail used to attach the backboard to the case, and the pieces are also glued to the backboard with hide glue. Another of my S.B. Jerome clocks has a similar feature. In the case of the latter, the decorative paper was crudely draped over the added wood piece. In the case of the clock in this posting, the wood pieces were added after the paper was glued to the backboard. From the back (outside) of the clock, there’s no evidence of mounting screws ever penetrating the backboard. The only screw that does penetrate through the backboard is the one holding the alarm bell. Were the wood pieces added at a later date, after the mounting screws lost purchase in the backboard, or are these an original feature of the clock? And, if added later, why would it have been necessary to add one for the gong base? Unlike movement mounting blocks, which were removed repeatedly to service the movement (leading to deterioration of the backboard), there would have been no reason to remove the gong and no reason to expect a problem holding the gong base to the backboard.

Another atypical feature of this clock is the door latch. Most S.B. Jerome shelf clocks I’ve seen have either a latch engaged by a door knob or a hook mounted on the side of the case. The latch on this clock is a strip of brass under tension that engages a small pin inside the door frame. In addition, it has a knob made of a composite material screwed to the door. The design elements of the knob are identical to the knob on another of my S.B. Jerome clocks, except that the latter turns a latch.

The hands do not match, and I don’t know which (if any) is original to the clock. Aside from the uncertainty about the hands and the wood pieces attached to the backboard, I believe everything else is original.