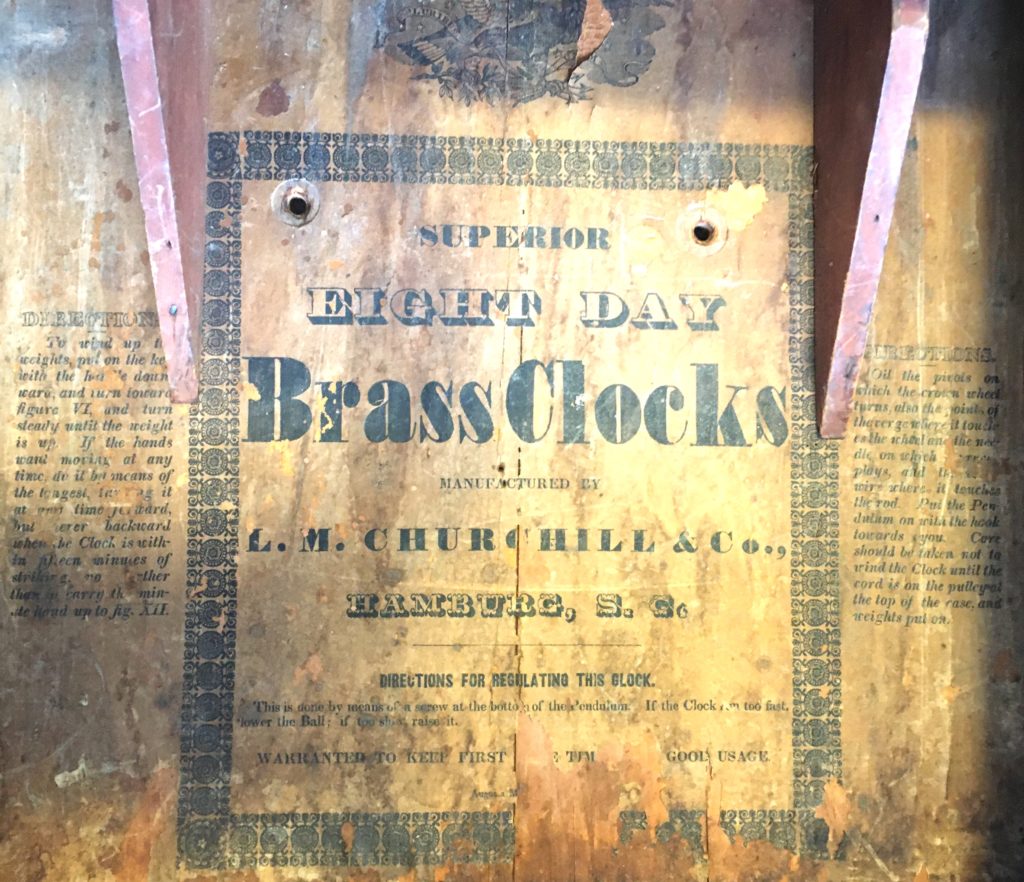

This 8-day column & cornice clock was made by L.M. Churchill & Co. of Hamburg, SC (present-day North Augusta). L.M. Churchill & Co. was a company set up by Chauncey Jerome to assemble clocks made at his factory in Bristol, CT. This was done to avoid tariffs imposed by southern states on merchandise coming in from the north. The company was in business from around 1837-1838. As an aside, Noble Jerome filed his patent application for improvements to the strike train of a 30-hr movement from Hamburg on June 10, 1839. Noble Jerome’s patent transformed the industry.

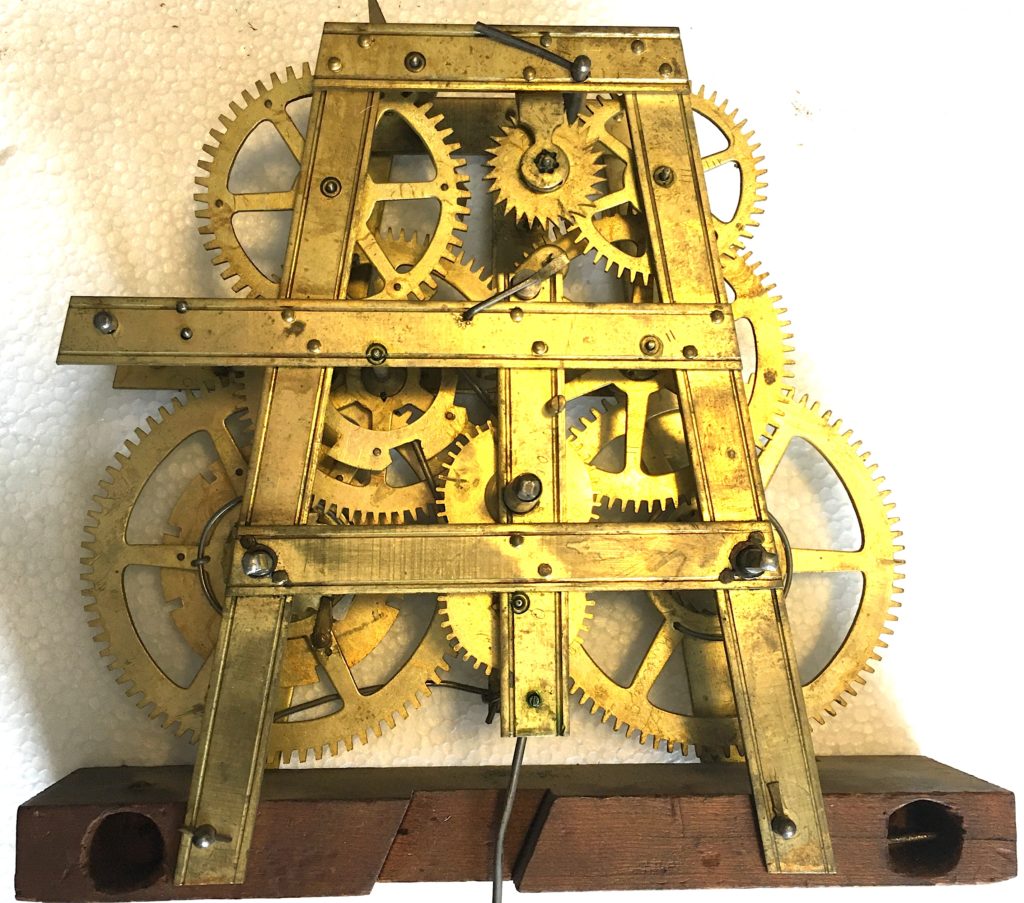

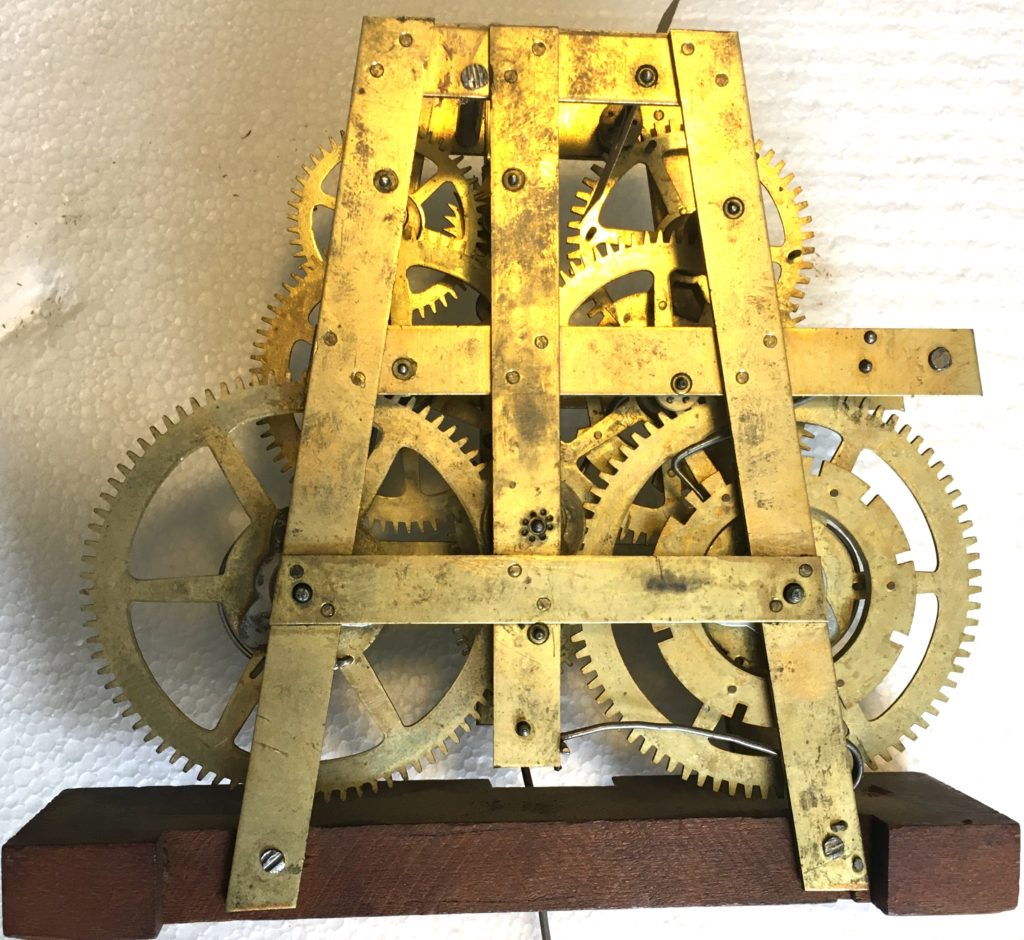

This clock does not utilize the Jerome patent. Instead, the 8-day movement is an Ives A-frame, rolling pinion, brass strap movement. My C.&N. Jerome triple-decker from around the same time also has this movement. 8-day Jerome clocks from this period (whether labeled C.&N. Jerome or L.M. Churchill & Co.) had either the Ives movement or a Jerome rack & snail movement. In his comprehensive monograph on Joseph Ives, Jim DuBois speculates that this A-frame movement might be one patented by Ives in 1836. However, he notes that, beyond the A-frame shape of the plates, the movement does not introduce elements not found on other movements by Ives. Records of the 1836 patent have not survived. The 1836 patent is one of nearly 10,000 patents that were lost in a fire in December 1836.

The label was printed by the Augusta Mirror, which was in business 1838-1841. The limited overlap in histories of Churchill & Co. and the Augusta Mirror indicates the clock was made in 1838.

One of the interesting features of this clock is the zinc dial with painted spandrels. I believe the dial is original. While not common, similar dials have been reported on the NAWCC message board by RMarkowitz and Sooth, the latter in a C&N Jerome wooden works clock. This is the first one of these dials in a Jerome clock that I’ve come across in person. Clocks made by Jerome a year or two later with Noble Jerome’s 30-hr patent movement often had a plain zinc dial with inked numerals. In these later clocks, rather than placing the painted spandrels on the dial, Jerome placed them on the upper glass in a manner that pleasingly framed the dial.

Condition-wise, the main problem with the clock is the lower glasses. The glasses actually appear to be original, but the reverse-painting is a much later addition. In places, paint overlaps the old putty. The hands are also not original, and the clock once had feet. Based on the differential oxidation on the base, I believe it had bun feet.

The clock came with an intriguing story (and I’m a sucker for clocks with stories). The seller told me that she bought the clock at an estate sale in Seal Rock, OR a few years ago. When purchased, it came with the book Fortunes are for the Few, Letters of a Forty-niner, by Charles William Churchill (edited by Duane A. Smith & David J. Weber). Notice more than a slight similarity between the names of the Hamburg clock maker and the author of the letters? The mystery lies in the connection, if any, between the two Churchills. Levi Merrill Churchill was born in 1811 in Boonville, Oneida County, NY. Charles William Churchill was born in 1822 in Lawrence County, OH. In February 1842, C.W. Churchill arrived in Augusta, GA to work in John Dunlap’s store. The position was arranged by William Churchill, C.W.’s uncle, who lived in New York (I believe). What was his uncle’s connection to Augusta, GA? Beyond sharing a last name and geographic proximity (just across the Savannah River from each other), my wife (the genealogist) and I have not been able to tie the two Churchill families together.

Is it possible that C.W. purchased the clock while living in Augusta? In letters to his brother, Mendal, it’s clear that C.W. did well enough that he was able to send money to his mother. Excerpts from several of his letters written in Augusta are presented in the book. None of those mention a clock. I contacted the San Diego Historical Society about obtaining copies of the letters written in Augusta, and they, for a small fee, sent me all 10 of the Georgia letters, plus a few others written around the same time. Frustratingly, not a single mention of a clock. In 1849, C.W. left for the gold fields of California by steamship. If he owned the clock, it’s extremely unlikely he would have taken it with him to California. He died in 1855, and, according to probate records, he had few possessions (again, no mention of a clock).

I’m left with a mystery. Is there even a connection between the clock and C.W. Churchill? The fact that C.W. lived just across the river within four years of the manufacture date of the clock is quite a coincidence. If it was C.W.’s, perhaps he dropped it off with his brother before heading west to seek his fortunes in the gold rush. Or is it possible that the clock belonged not to C.W., but to his brother, Mendal? Mendal was an officer in the Union Army and was in Sherman’s campaign through the south. Could Mendal have liberated the clock as war booty?

The clock is pictured in the June 2009 NAWCC Bulletin (No. 380) in a write-up by Chris Bailey. Unfortunately, I have been unsuccessful in attempts to contact the owner of the clock at the time of the article. One question I’d like to get answered is whether the book of letters was with the clock in 2009, or if the two hooked up between 2009 and the time the clock was sold to the previous owner a few years ago.