Before discussing my most recent acquisition, I need to go over a little history about Chauncey Jerome. Sometime around January 1844, Jerome started making cases in a converted carriage factory in New Haven, CT. The rest of his manufacturing operations, including movement making, were located in Bristol, CT.

Before discussing my most recent acquisition, I need to go over a little history about Chauncey Jerome. Sometime around January 1844, Jerome started making cases in a converted carriage factory in New Haven, CT. The rest of his manufacturing operations, including movement making, were located in Bristol, CT.

In Jerome’s words:

“In the winter of 1844, I moved to the city of New Haven with the expectation of making my cases there. I had fitted up two large factories in Bristol for making brass movements only the year before, and had spared no pains to have them just right. My factory in New Haven was fitted up expressly for making the cases and boxing the finished clocks; the movements were packed, one hundred in a box, and sent to New Haven where they were cased and shipped.”

On April 23, 1845, most of his factory buildings in Bristol were destroyed in a fire. According to Jerome, they had “somewhere between fifty and seventy-five thousand brass movements in the works, a large number of them finished…” As recounted by Hiram Camp (Jerome’s nephew and shop foreman):

“We had at this time large quantities of movements and parts in progress. The windows were opened and the movements pitched out on the ground enough to fill an office building that stood outside that was sixteen feet square. The tools to some extent were gotten out, but all presses and dies went through the fire.”

Rather than rebuilding in Bristol, Jerome shifted his operations to New Haven. From early 1844 until April 1845, Jerome’s clocks typically contained movements with a Bristol maker’s stamp that were in cases with New Haven labels.

Describing the efforts to resume full production in New Haven, Camp says:

“There was a blacksmith’s shop 100 feet long and 30 wide, so measures were taken immediately to raise the roof and fit that for the movement work…So things went forward and early in the fall we were in shape and work going in New Haven.”

What happened to those movements saved from the fire? One such movement, designated as a type 1.81 by Snowden Taylor, has been reported by me in the NAWCC Bulletin. These type 1.81 movements are obvious candidates for “fire” movements, because they have non-standard strike levers and a stamp with the line indicating “BRISTOL, CONN” ground off. It appears that, even though Camp said all presses and die went through the fire, the maker’s stamp must have been saved. There are other candidates for “fire” movements, as well. These have “mismatched” plates: front plates with features of Bristol plates and back plates with New Haven features. These are not a case of a repairperson intentionally or inadvertently swapping out plates, because the holes drilled in both plates for the pivots are in the positions found on New Haven, not Bristol, movements. In other words, blank Bristol front plates saved from the fire were taken to New Haven and drilled to marry with a New Haven back plate.

As an aside, when using Snowden Taylor’s movement identification scheme, there is no difference in noted shop details between a Bristol and a New Haven type 1.311 movement. However, I’ve analyzed examples of both, and there are differences. One difference visible to the eye is the vertical member forming part of the T in the front plate: it is approximately 19 mm wide on a Bristol plate and 16 mm wide on a New Haven. Differences in back plates are subtler, but they do exist.

Now to my latest clock. It is a kissing cousin to one previously posted on my website. It’s best described as a box clock with a raised, flat molding on the front. Prior to my recent purchase, the only clocks like this that I have seen have had Bristol-made type 1.211 movements and Bristol labels that date to around 1841.

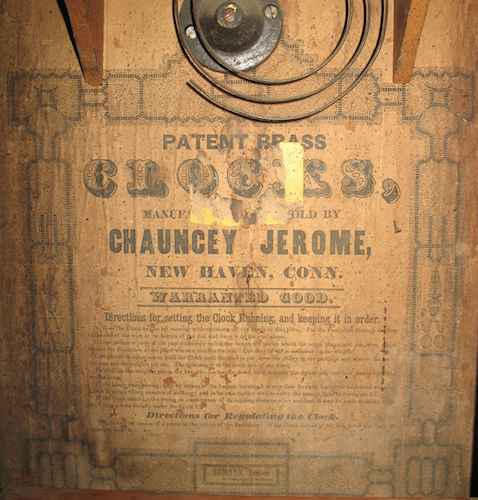

Early New Haven label printed by John Benham (55 Orange St.). Benham first appears at that address in the 1845 New Haven directory; in 1844 he was at 68 Orange St.

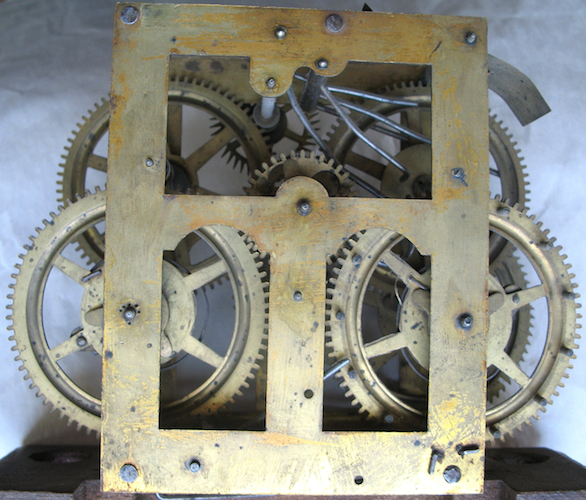

Front view of the movement, which is a pairing of a type 1.311 Bristol front plate with a type 1.311 New Haven back plate, and likely represents the using up of parts salvaged from the fire along with newly manufactured parts in New Haven. The movement has the standard “CHAUNCEY JEROME/NEW HAVEN, CONN/USA” maker’s stamp.

Rear view of the type 1.311 movement, made in New Haven. From the history I detailed above, a New Haven-stamped movement in a New Haven case dates no earlier than April 1845 (based on Camp’s account, likely early fall after ramping up production in New Haven). The combination of the Bristol and New Haven plates leads me to believe the clock is one of the earliest assembled after the Bristol fire. Note that the front and back plates were drilled to receive an internal alarm, although one was never fitted to this movement.

The case, although very similar to the Bristol version previously reported, is not identical. The dimensions of the two are as follows: Bristol (24 3/8” x 14” x 4 3/16”; top and bottom molding width = 1 13/16”; side molding width = 1 7/8”); New Haven (24 11/16” x 14 ¼” x 4 1/8”; molding width = 1 ¾”). The New Haven version is slightly larger but has narrower molding. Another difference is that the outer edge of the raised molding on the New Haven is flush with the box it’s attached to. The outer edge of the molding on the Bristol, on the other hand, is not flush. The box that the molding is attached to is narrower (13 13/16”) than the molding (14”).

The veneer on the New Haven case is very plain. Not only that, but the grain runs parallel to the long dimensions, which is unusual. Aside from the veneer on the bottom molding, I believe all of the veneer is original. The original veneer may be maple.

The tablet is an absolute killer, with free-hand characteristics similar to those in many New York-cased clocks, as well as some that are often paired with Fenn stenciled tablets.

A characteristic that I have seen on some (but not all) weight-driven Jerome clocks dating to 1845 is the use of what I refer to as “pin” hinges. Rather than being the typical butt hinges that are attached with screws, each half of the hinge has a sharp pin that is driven into the doorframe and the case.